Van Gogh And Expressionism At Neue Galerie

by Gordon Fitch

The Neue Gallerie is a small "boutique" museum at Fifth Avenue and 86th Street devoted to the German and Austrian art of the early 20th century. The current show, "Van Gogh and Expressionism", which in effect occupies the whole of its exhibition space, is devoted to the relation between Van Gogh and the Expressionists (and thus Modernism). The relation is familial, indeed, it is held to be paternal and filial, following the words of one Expressionist (Herman Max Pechstein) who called Van Gogh "the father of us all." The children, however, turned out to be rather variegated, some looking a lot like their parent and some not: Schiele, Klimt, Kandinsky, Kokoschka among the big names, and many lesser-known but very interesting progeny as well. Each of them took something different from Van Gogh, and took it a different way. Surprisingly, especially surprisingly after you see the show, we learn that this obvious, indeed striking relationship has not been much explored by critics and theorists.

The Neue Galerie is not large; the curator of a show there must take care to be effective. There is no room for throwaways, fillers or asides. In this case the the guest curator, Jill Lloyd, put together 80 paintings and drawings and some ancillary material in a highly resonant way. It is a larger version of a similar exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam recently. The relatively small size of the space may have been a benefit in the case of the present exhibition. For one thing, given the heavyweights involved, with more considerable space to manoeuvre in it would not be hard to find oneself presenting a collection of vaguely-related onrushing warhorses and simply running down the viewer. For another, one has a more sophisticated audience to deal with: the Neue Galerie is too small to host blockbuster shows drawing innumerable confused tourists with an afternoon on their hands. The people who arrive know more or less what they're looking at and you can show them something intelligent.

That is what the curator did. The pictures are gathered in sets which are sometimes thematic, sometimes technical, sometimes emotional or intuitive — sometimes one might even same the connecting thread is a color — reflecting the different ways the Expressionists responded to Van Gogh's work, which began appearing in Germany in 1901 and caused a sensation in the art world there. For instance, one series starts with a street and some houses by Van Gogh; the theme is repeated by several other artists, not only as to the general theme, but to some extent in the color as well. Again, we see one of Van Gogh's popular sunflower bouquets next to one by Schiele; but in Schiele's work, the vigorous sunflowers of Van Gogh's picture are darker, perhaps dusty, certainly ready to die (a picture which Schiele also supplies us with, although not at this exhibition.) Now the relation is both formal and thematic — and probably narrative as well; Schiele is said to have seen himself as an artiste maudit in what he imagined to be Van Gogh's style.

Vincent Van Gogh, Egon Schiele: Details from Sunflower paintings

A nice touch in addition to the paintings is a corner dedicated to books, posters, letters and the like connected with bringing the gospel of Van Gogh to the Germans. It includes a couple of letters about exhibition or sale possibilities to Jo Bonger-Van Gogh, Theo's widow, who was probably responsible more than anyone else for the preservation of Vincent's work unto triumph, a task to which she dedicated most of her post-Van Gogh life. It is like seeing the bones of the saints.

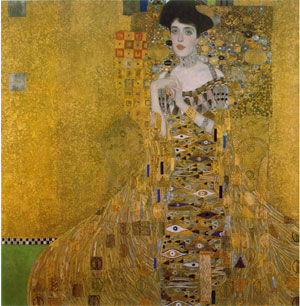

Interestingly, the museum maintains as its centerpiece — "our Mona Lisa" as founder Ronald S. Lauder called it — Klimt's famous "Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I", for better or worse an overwhelming work made of gold and sliver as well as oil paint for an enormously wealthy magnate, subsequently stolen by the Nazis, placed in an Austrian museum, wrested from the Austrians through a long and arduous legal process, and finally sold to Lauder not long ago for a reputed $135 million. Everything in its space (and out in the hall as well) must deal with it and its repute; and the curator did not choose to set Van Gogh up to challenge it. Van Gogh in Klimt, though? Well, although Klimt does not seem to be much concerned with Van Gogh's issues of spirit, technique, color, and so on, one thing about Klimt's picture relates directly to Van Gogh, and that is the fact that the two-dimensional spatial layout of the painting dominates its design. One sees that as well in Van Gogh, a breaking-away from the domination of optical perspective, although in Van Gogh there is almost always at least a nod towards it. Later, this breaking with the dominance of perspective and the insistence on the reality of the picture plane will become tremendously important to painters. In Klimt, however, and in Van Gogh as well, it's not a manifesto, it seems to be just something that happened to happen on the way to making a painting. High Modernism is still around the corner.

Gustav Klimt, "Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I"

(One should note as well in regard to the relation between these two artists that Klimt was also one of the first to recognize Van Gogh's worth and was instrumental in bringing his work to Vienna and publicizing it there.)

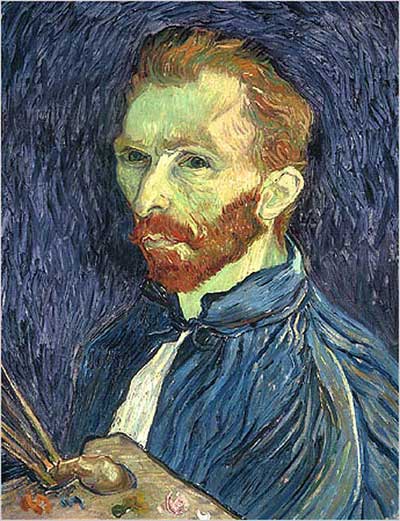

The most striking room is that containing portraits, mostly self-portraits, including two by Van Gogh. There a rather dark drawing by Lovis Corinth, followed by Van Gogh in a straw hat, looking pretty much like a farmer, then some rather more radical works by Kirschner and Herbert Boeckel, followed by two striking portraits by Emil Nolde. Now, here we come to an interesting transition of organizing principle, for up until Nolde we have been observing an increasing reliance on Van Gogh's techniques, mostly his breaking-up of the image into vigorous strokes of strongly (not always brightly) colored paint, his complete willingness to force color to do his bidding in green and purple shadows; his "children" do likewise. But Nolde was more than technically indebted to Van Gogh; he also believed in the spiritual side of Van Gogh's work. Thus we turn the corner from Nolde's severely fragmented yet strong and coherent head of a woman and step up to his weirdly luminous self-portrait with surrealistically blue, enlarged eyes — and then comes its certain progenitor, Van Gogh's self-portrait, the most famous one, where he peers at us out of a blue whirlwind, his face pale and greenish-tinged, gaunt, intense, his eyes ice-blue and totally alive, more alive than anyone you are likely to meet this week, in recognition and challenge.

Vincent Van Gogh: Self-Portrait (1889)

I thought the show had another side besides showing us how Van Gogh affected a lot of important German artists: it helped me see new things in Van Gogh, and I've been looking at Van Gogh works (all right, usually as reproductions) all my life. This or that element is now something that comes forth more prominently in the works of Kandinsky, Kokoschka, Schiele, Klimt, Nolde, Kirschner, Pechstein and the others; they show the possibilities and connections of the originals, some of the places they will lead to. One doesn't expect the sun to shine additionally by virtue of its planets, but there it is.

Shall I say you must see this show? Yes, you must see it. I've told you only half of what's there. Even for New Yorkers jaded with the surfeit of museums and galleries, it is a gem. It will run until July 2, 2007. Besides the galleries, the museum also contains a bookstore where you may find things you won't see elsewhere, a design shop, where objects based on the famed Viennese designers of the period are available, and possibly the most popular feature, the Café Sabarsky, which "evokes the great fin-de-siècle cafés of Vienna." Sadly your reviewer could not try it out, since there was a long line waiting to get in the whole time of his visit. But we shall lay siege in the future.

Text copyright © 2007 Gordon Fitch

back to Contents page

back to Contents page