Olga Maryschuk:

My Neighborhood

by Diana Manister

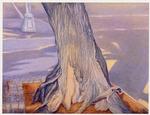

Olga Maryschuk: Elm

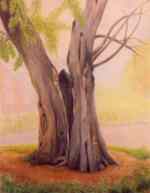

Olga Maryschuk: 7th Street Locust East

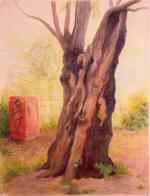

Olga Maryschuk: 7th Street Locust West

|

Olga Maryschuk: My Neighborhood Exhibition of Prints and Pastels New York Public Library, Tompkins Gallery 331 East 10th St. NY NY 10009 |

Tompkins Square Park , on the Lower East Side of New York City, has been the scene of many marches and protests and political actions. Unions, civil rights demonstrators, immigrant activists and most recently the riots of 1988-89 over the rights of the homeless to erect shelters and live in the park, and the park's stalwart trees witnessed it all. Artist Olga Maryschuk, who spent many childhood hours at the Tompkins Square Library and playing under the trees in this park right across the street, has rendered a series of respectful images of these old friends, portraits, really, that show the scars and injuries these ancient trees have sustained in their determination to survive in an urban environment. Titled "My Neighborhood," the exhibit, installed in the well-appointed gallery of the Tompkins library during June, hangs only yards from the actual subjects depicted.

Originally a salt marsh, Tompkins Square Park was filled in at the direction of New York governor Tompkins during the War of 1812, to serve as a fortification against the British. When he freed the slaves in the state in 1827, the park was named for him. Roots of water-loving weeping willows even today reach deep into the old marsh. One of the benefits of Maryschuk's show is to bring to public attention the devotion and hard work of the East Village Parks Conservancy, a community organization that maintains this lush greenery. It is rare today to see a group of American Elm trees, since the incurable Dutch elm fungus swept across the U.S. in the 1930s. Despite the loss of over 30 of its elms, Tompkins Square Park is still shaded by towering Elm canopies, thanks to Convervancy volunteers who inspect the trees with binoculars every Saturday for signs of bark beetles that carry the disease.

Exhibiting prints and oil pastels, the artist takes as her subjects not only her beloved elms, locusts and oaks, but other aspects of this unique neighborhood's character. A series of monoprints pictures a local folk art assemblage of flowers, pinwheels and fanciful objects made from sheared aluminum cans mounted on a chain link fence, a mongo garden that blooms more densely year by year. Another print series consists of impressionistic views of the top of the local Con Edison building, pictured in the changing colors of varying times of day and night, a lower East Side version of Monet's cathedral facade. But the stars of the show are a series of medium-sized oil pastels of gnarled, wounded, aged survivor trees, with limbs sheared off by lightning, or bark shorn, coiling, leaning, reaching for light and water.

Trees, from that infamous apple tree in Genesis, have always figured prominently in human life, culture and religion. Tree worship was a feature of the old religions of Europe and Asia: Yggdrasil was a refuge for Odin, the Buddha reached Nirvana under the Bodhi tree, Vikings worshipped the World-Tree, and the Celts' Old World sanctuaries were sacred groves. An important influence on modern literature, notably T.S. Eliot, and the work of Jung concerning the deep unconscious, was a study of the tree in ancient mythologies, The Golden Bough, by George Frazer. Trees evoke primitive modes of thought, superstition, sympathetic magic and are used, often very successfully, in folk medicine. Pertinent to today's world, their survival is a major factor in alleviating global warming.

Maryschuk's renderings are sensitive to these qualities, and the poignancy of the struggles our tree companions undergo in the city. "Elm at 10th and B", the image that appears on the show's announcement, contrasts the rippling, organic trunk with the characterless smooth pavement and aluminum pole that lack the tree's vulnerability and sentience. A grid of paving stones imprisons the trunk in its geometry, limiting its access to water to a small rectangle, suffocating the ground. No cicadas will emerge from under this cement. Sunlight in the picture is shown to be meagre, the tree leaning into it as if to absorb as much as it can.

"7th Street Locust East" is eerily anatomical, exploiting all the metaphorical power of visual poetry, the simultaneous implications and repeated patterns in nature. While remaining a tree, it is also mammalian, bearing labial and phallic forms as well as finger and spine-like appendages, as if the artist were asking the viewer to notice the commonality of living things. A mysterious black figure peers from a split in the tree's trunk, a dark, haunting, animistic presence that resonates profoundly with Native American, African, Brazilian and Asian mythologies that attribute a spirit or soul to each tree, as well as sensitivity to pain. (The woodsmen of Old Germany asked a tree's forgiveness before cutting it down).

Also richly mysterious is "7th Street Locust West," a battered sage of a tree that seems to express in some nonverbal language a hidden knowledge. This impression is reinforced by an unidentifiable plinth covered with runic writing that stands alongside it. The two together might be the setting for a Druid ceremony, perhaps, or for 16th Century alchemists paying reverence to the Tree of Life. Of course, it's only a beat-up old tree next to an electric transformer in a metal box, but still....

Now, when thousands of acres of forest are clear-cut annually for lumber, and housing developments, malls and parking lots replace wooded areas, it is moving to experience works of art that bear witness to the value to human life and history of these, our ancient companions. A permanent exhibition of her Olga Maryschuk's work can be seen on the web at http://www.paintingsdirect.com

Images copyright © 2004 Olga Maryschuk

back to Contents page

back to Contents page